—81→

—[82]→ —83→

In his recent and invaluable Critical Guide to Nazarín Peter Bly (62-63) writes of Andara:

A footnote (63) is appended to this, which I quote in full:

All of this is perfectly true. Galdós makes a point of telling his readers early on that the name Andara derives from Ana de Ara, and it is difficult to set aside the local resonances of the statue of Santa Ana and the name of the street. And yet, as Bly himself has noted, confusion over names appears to be the name of the game in Nazarín: Madrid is given half a dozen names, Chanfaina four, and Nazarín three, plus all the descriptive variants such as «el buen padrito». The confusion over names seems to go hand in hand with the confusion over the identity of the narrator, but that is not so much my concern here as to set out briefly another group of associations which, I believe, played a crucial role in Galdós's naming and describing of some of the characters in this novel.

For most readers of Nazarín who know well the North of Spain (and especially the Cantabria/Asturias border), the name Andara will have resonances of a very different order from those described by Professor Bly. Not far west of Potes, at the beginning of the Picos de Europe, is the Sierra de Andara. Mountaineering books speak of the Macizo de Andara, and maps show either the Lago or Pozo de Andara, according to their date of publication (the lake dried up owing to a man-made leak). At the time when Galdós was writing Nazarín -at San Quintín, in Santander, as Benito Madariaga (400) informs us, and as Galdós himself stated- he was in the position of being able to draw on nearly twenty-five years of association with Pereda and the Montaña. In his early novels -most notably in Doña Perfecta and Gloria, but also in Marianela- the range of «santanderino» sources and echoes is wide and obvious. In later novels that range is far more limited and less evident. The letters between Galdós and Pereda attest to the former's regular use of Montaña material in his novels, and most —84→ of this has been commented on by Benito Madariaga. Interestingly enough, it was Madariaga who noted, in his edition of Cuarenta leguas por Cantabria that there is a possible connection between the place-name Andara, as used by Galdós in this travelogue, and the character Andara in Nazarín and Halma. The language of this context is important, as will become apparent later in this note: «y en último término las descomunales crestas de Andara, último esfuerzo de la tierra para llegar al cielo» (74). For Madariaga there is no doubt about the linkage in Galdós's mind: «Este nombre fue utilizado por Pérez Galdós y aparece en Nazarín (1895) y Halma (1895) para denominar a uno de sus personajes» (74, note 138)96. To my mind the fact that Galdós referred in these terms to the Sierra de Andara in Cuarenta leguas is not sufficient evidence in itself to postulate the certainty of a linkage between this name and the character Andara. But the story does not end there; indeed, it may be just the beginning...

Peter Bly has commented, as we saw, on the confusion attaching to the name Andara, mentioning the lack of an indication as to the correct stress-point, save in the Alianza edition. The place-name Andara does not, in accordance with the convention regarding capitals, normally bear a written accent, though it is always stressed on the first syllable. Most reasonably well educated Spaniards, even those unacquainted with the Sierra, Lago or Pozo de Andara, would tend to stress it on the first syllable, taking it for granted that the capital accounts for the lack of a written accent. The play that Galdós makes with the Ana de Ara derivation -«(a quien llamaban así por contracción de Ana de Ara)»- immediately throws a spanner in the works with regard to any dogmatic assertion that the name must be stressed on the first syllable, since, if we are to take Galdós's statement at face value (and not as a further ironic twist in the already lengthy, complicated and confusing ambiguity of resonances called forth by multiple names) the contraction of the name Ana de Ara would have to be stressed on the second syllable. But the confusion perceived by Bly has another dimension. Andara's name, stressed wherever, is the only main name for a major character which is italicized in the text, apart from Chanfaina. Thus we are always conscious, when Andara is «on stage» alongside, say, Nazarín and/or Beatriz, of a difference of kind; Andara, with its italicization, draws attention to an attribute, as with the Peludos and the tía Chanfaina or el Pinto, or it underlines the fact that this name is not her true or full name (which presumably is Ana de Ara) but her popular or used name, the one by which she is known. What sort of association or image may Galdós have had in mind in choosing and using the name Andara? Peter Bly rightly, I believe, discounts the «andar» connection. Andara is «andariega» and «andarina», but so is Beatriz, and so is Nazarín. Galdós tells us outright that the name is a contraction of Ana de Ara, but is that the sum of the resonances produced by Andara? I think not.

In Cuarenta leguas por Cantabria, dating in its first published version from late 1876, Galdós wrote, as we have seen, of «las descomunales crestas de Andara, último esfuerzo de la tierra para llegar al cielo». Where would Galdós get his impression of the Sierra de Andara from? He would of course see it for himself, but we know that his excursion with Pereda was brief and highly selective. Indeed, his jottings en route were in all probability a combination of his own observations at first hand plus the promptings over detail of his travel companion, Pereda, who knew this part of the Montaña relatively well. Be that as it may, in November 1876, Galdós writes to Pereda telling him of the loss of those selfsame notes or jottings and asking if he —85→ would be willing to add to the proofs or «pliegos sueltos» for La Tertulia all the names of places that he, Galdós, had forgotten, also that «le quite y le ponga todo lo que crea conveniente»97. We cannot now know exactly what Pereda's emendations and additions were. What we do know for certain is that the average well-informed «santanderino's» perception of Andara and the Sierra de Andara entailed awareness of remoteness, wildness and loftiness. When the name crops up in nineteenth-century Santander journalism it is with these characteristics at the forefront. «Costumbrista» writers of the region use it almost synonymously with the notion of the inaccessible and the outlandish. When Pereda refers to the Sierra or just to Andara, it is either with these features in mind, or in connection with the «oso pardo», which was common in Liébana at the end of the nineteenth century. A typical example of the latter would be the reference in Peñas arriba: «Tuvo de ella dos hijos como dos oseznos de Andara, de cuya educación no se cuidó cosa maldita» (186).

That this range of associations would necessarily be assimilated by Galdós during his twenty-five odd years of acquaintance with the Montaña and its major literary figures, prior to the publication of Nazarín, cannot now be proved or disproved. But given what Galdós wrote about Andara in Cuarenta leguas, probably with the help of Pereda as the man on the spot, it would seem unrealistic to dismiss out of hand the possibility of this Andara being the source or part-source of the Andara of Nazarín. If we think for a moment of some of the characteristics of Andara as described early on in the novel -cat-like and feral («con rápido salto de gata cazadora»); hostile and wild («tarasca herida», «tarasca», «soy muy loba», etc.); fleeing from the authorities and presenting a figure which is outlandish and primitive- we may make a connection between these and the resonances given off by the name Andara for Pereda, for «santanderinos», and possibly for Galdós. However, it is not vital to my case that we should make that connection, though I consider the likelihood of the connection to be strong. We can get at the linkage by other means, which will in turn make a stronger case for the wild and hostile nature of the Sierra being reflected in the figure of Andara.

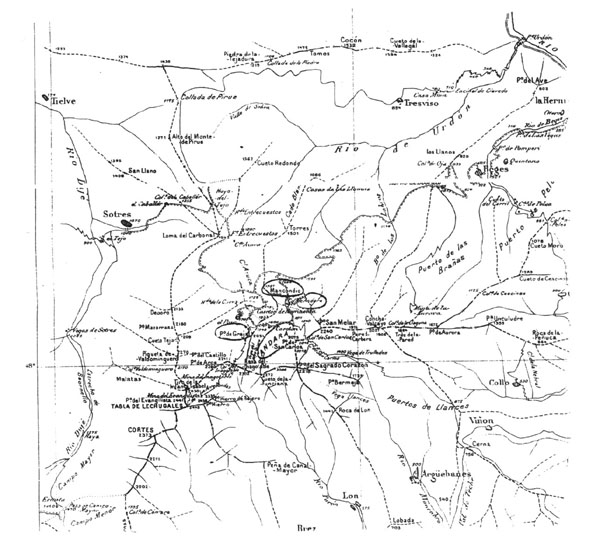

Peter Bly, in dealing with the character of the dwarf, Ujo, offers a footnote telling us that Ujo is the name of a village in Asturias (71, note 19). Because his coverage of the name Andara does not take into account the fact that Andara is a Cantabrian peak and range, demonstrably known to Galdós, Bly misses inevitably the additional fact that Ujo and Andara are quite close to each other. If Galdós when dreaming up his characters for Nazarín, had cast his mind back to his reference to Andara in Cuarenta leguas and had then checked with a map of the area, he could easily have seen the two names of Andara and Ujo in close proximity. Whatever the explanation of Galdós's use of these two names in Nazarín, the text itself presents the bearers of these two names in similarly close proximity. It is Andara and Beatriz who had seen the «ridículo enano» Ujo when they were in the church with Nazarín98. It is Beatriz who strikes up a friendship with Ujo at first, but it is Andara who laughingly says: «¡Si es Ujo, mi novio! [...] Ujo, prenda, nano mío» (IV, v). For this reader at least the undoubted existence of Andara and Ujo as place names, separated by a few kilometers, points clearly to Galdós's having incorporated them, in a new incarnation as characters, into his novel. Something more remains to be disclosed, however.

In 1875, twenty years before the publication of Nazarín, there was published in Madrid a semi-novelized work entitled La Osa de Andara99. This account, highly coloured and sensationalistic, was based in part on local anecdotes centred on the —86→ Andara area. Briefly, it tells the story of a woman/creature, known locally as «la Osa de Andara», who lived a wild and solitary existence, fending for herself, tending her goats, shunned by the villagers of the region because of her fierce and outlandish appearance; she was covered in dense hair and ate raw the kids provided by her goats. This same first account tells us: «Vive en el Grajal y Mancondio, en verano, y las cavernas de la entrada de Ujo, por la parte de Hermida, en invierno»100. Such a picture of a savage outcast from society (though this view is radically transformed in some later versions of her story101) could not but make her a nine-day wonder in Santander. Even if Galdós did not read or know of the book La Osa de Andara -and it must be said that the reference to Ujo in the above quotation is highly suggestive- it is almost unthinkable that he could fail to see the newspaper coverage or hear about «La Osa» from friends such as Pereda. It would seem probable that he did not know of the story when he wrote Cuarenta leguas, otherwise he might have referred to it when he writes of «las descomunales crestas de Andara». It is not the sort of story that Galdós would willingly have passed over in writing a pot-boiler such as Cuarenta leguas.

So, supposing that Galdós might easily have had access to the tale, or Its essentials, through newspapers or his Santander circle, what has this to do with Nazarín? Quite apart from the further specific references to Andara and Ujo provided by this possible source, the linkage with Nazarín may take two forms. Firstly, the tale of «La Osa de Andara» reinforces the wild and primitive resonances ranged around the mere name Andara and strong in the popular imagination; Andara in the novel fits in neatly with this context, representing «farouche» characteristics, but also aspiring feverishly, with Nazarín and Beatriz, to the heights (we might recall here «y en último término las descomunales crestas de Andara, último esfuerzo de la tierra para llegar al cielo»). In the second place, we can locate in Nazarín a group of names and associations which seems to promote rather gratuitously the twin notions of beariness and hairiness. When the narrator recalls his first knowledge of tía Chanfaina's boarding house he mentions the «calle de las Amazonas» and proceeds via the «amazonas» to wondering what they were after in «los Madroñales del Oso» (I, ii). There is a later reference to going to buy wine «a la taberna de la calle del Oso» (II, ii). Then we are told that Nazarín's friends in the Calle de Calatrava are called «los Peludos», referred to shortly after as «los infelices y honrados Peludos» (II, vi). In no time at all the Peludos are separated into «el Peludo» and «la Peluda», which is a little confusing because there is already in the narrative a companion of Andara's called «la Pelada». We are not informed why Nazarín's friends are called «los Peludos», though the reason why Andara's companion is called «la Pelada» is self-evident. We are not told either why the street is called the «calle del Oso» or the area «los Madroñales del Oso». My theory would run as follows: Galdós was drawing without method or pattern on a range of associations harking back to his own Cuarenta leguas por Cantabria, corrected by Pereda. For any of a number of reasons he singled out the names of Andara and Ujo -as we have seen, he could have spotted them given adjacently on a map, or he could have read La Osa de Andara, or Pereda could have mentioned the two names in conjunction with the Picos- and the use of these names triggered off echoes of tales of bears and bear -hunting (of course, Pereda wrote Peñas arriba in the year before Nazarín appeared102) and more particularly cast his mind back to the legend and the reality of «La Osa de Andara».

None of this invalidates what Peter Bly says in his Critical Guide about Ana de —87→ Ara, but a case can be made for two levels of association and two levels of resonance being cultivated at the same time, one of them based on what Galdós chooses to tell us very simply at an early stage («a quien llamaban así por contracción de Ana de Ara») and the other deeply seated in Galdós' own memories and reading, and formulated in an apparently random way. Perhaps this is not the best moment to mention that Santa Ana is also the name of a peak in the Picos de Europa, not too far from the other places we have been considering...!103

University of Birmingham

NOTE: Beges, where the «Mujer osa» came from and where she lived in winter, is near La Hermida, about 65 kms. WSW of Santander and bordering the eastern massif of the Picos de Europa. El Grajal, Mancondio and the Sierra de Andara, and presumably Ujo as well, though it is not shown on the map (few names of caves are shown; «hoyo» and «ujo» are both used for names of caves; «ujero» is used in remoter parts of western Cantabria and eastern Asturias for «agujero») are just a few kilometers from Beges.