—91→

Although Galdó's liberalism in religious and political matters is well known, the standard biographies and major works of criticism concerning him make no mention of Don Benito's interest in and affiliation with the Movimiento Pro-Sefardita, to which a number of prominent Spanish liberals belonged during the early years of the twentieth century.186 Consequently, documentation of Galdós' support of this movement has, to date, consisted exclusively of the listing of his name by Jewish writers in their discussions of the movement. Now, however, through letters preserved at the Casa-Museo Pérez Galdós, it is possible to confirm Don Benito's pro-Sephardic activities, learn a few details concerning this aspect of his altruism, and note the effect of this involvement on his fictional creativity.

By the turn of the century, the relationship between Spain and her expatriate Sephardic communities, which -except for a brief period of enthusiasm and mutual contact after the armies of General Prim discovered Spanishspeaking Sephardim in Morocco during the 1859-60 military invasion- had for over four hundred years been one of almost total separation and mutual disdain, was beginning to change.187 Spain, crushed by her defeat at the hands of the United States and by the loss of the last important remnants of her empire, sought a new role in the international arena, one which would help her forget her humiliation and regain a bit of pride and prestige. On the Sephardic side, the pogroms in Russia and the decline of the Ottoman Empire had created a feeling of unease. More urgently, after four centuries of isolation devoid of invigorating contact with la madre patria, the Judeo-Spanish language had come to be thought of as a jargon and was clearly in danger of being abandoned by the younger generation in favor of languages of more utility and prestige, particularly French.188 The Alliance Israélite Universelle, for example, offered instruction exclusively in the French language and prohibited any use of Spanish in its schools. This, of course, portended the loss of Sephardic values and, in turn, the eventual loss of identity vis-à-vis other Jewish groups, especially the more numerous Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazim.

Both Spain and the Sephardic Jews had observed the success of the French-sponsored Alliance Israélite Universelle throughout North Africa, the Balkans, and the Near East.189 La madre patria perceived how much it increased French prestige internationally; the Sephardim realized that a similar program of cultural contacts with a Spanish-language instructional emphasis could counterbalance French influences and help them retain their language and cultural identity. Consequently, when Dr. Ángel Pulido Fernández, a physician and member of the Spanish Senate, launched his pro-Sephardic —92→ campaign in 1903-04,190 community leaders throughout the Sephardic world responded enthusiastically. Even Spain's new king, Alfonso XII, became a supporter of Pulido's program, which included the following:

1. Securing a population census of each Sephardic community, identification of its leaders, and details of its cultural and philanthropic activities by means of correspondence and a questionnaire.

2. Awarding of honors, such as medals and decorations, by the Spanish government to Sephardic leaders.

3. Appointing of a number of distinguished Sephardim as honorary Spanish consuls in their home cities.

4. Naming of judeo-Spanish writers and cultural leaders to membership in the Real Academia de la Lengua Española as «académicos correspondientes».

5. Awarding of literary prizes for judeo-Spanish writers (by such organizations as La Asociación de Escritores y Artistas).

6. Financial aid to Sephardic elementary schools, as well as contacts with youth groups, to encourage continued study of judeo-Spanish, but now in a revitalized form stressing the Latin alphabet and using Castillian as a model.

7. Commercial penetration of the judeo-Spanish literary market with Spanish classics and current publications (a program already somewhat successful in Morocco).

8. Stimulation of foreign trade (by Spanish Chambers of Commerce) not only with 500,000 Sephardim in key cities throughout the Mediterranean basin, but also, through them, with the non-Jewish populations.191

Letters preserved at the Casa-Museo Pérez Galdós reveal that Galdós cooperated with Dr. Pulido in helping Sephardic young people toward the goal of improving their Spanish by sending copies of his works to appropriate youth groups.192 Letters 1 and 2 (1904), concern the sending of such books to «La esperanza, una Sociedad Israelita española» of Vienna, The principal aim of this organization was to «mantener la lengua española y hacer posible a sus miembros la instrucción científica y literaria», and thus to replace their present «jargón yerrado y falto de toda regla» with «una lengua metódica, viva, rica y hermosa».193 Pulido said to Galdós, «En la regeneración del idioma ladino debe Vd. aparecer como uno de los escritores más dignos de ser conocidos y de servir de modelo» (letter 1, 20 February 1904). We do not know which of his own works Galdós sent, but we are certain that he did send some, and Pulido publicly acknowledged his contribution.194

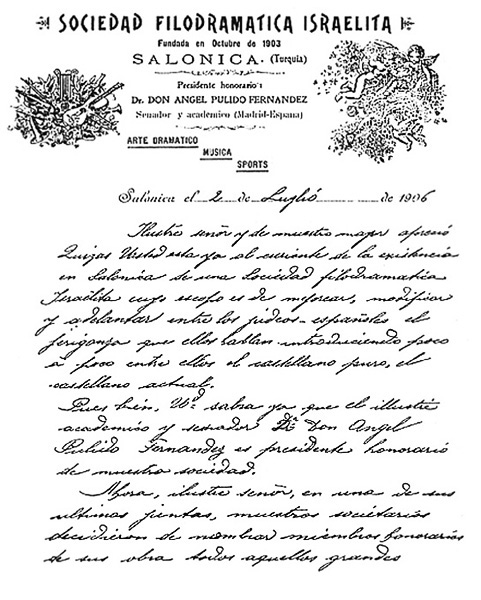

Letter 3 (2 July 1906) also contains a request for books. It is from the Sociedad Filodramática Israelita of Salonica and it tells Galdós, in addition, that he has been elected to honorary membership in that organization.

A letter of 22 October 1909 (letter 4) reveals that Galdós had received a newspaper from Constantinople containing an article about «el idioma judeo-español» and had passed it along to Dr. Pulido.

—93→A postcard dated Constantinople (letter 5, 12 July 1910) from the distinguished Sephardic publisher and dramatist, Sento (sem Tob) Semo, tells Galdós that he is sending him a copy of his «drama histórico, Don Isaac», along with reviews concerning it from Constantinople newspapers.195 He also asks Galdós' help in marketing the book in Spain.

Finally, we know that Galdós held membership in a Spanish-Sephardic organization. A letter (letter 6, dated only 17 March) from Doña Carmen de Burgos Segui, a prominent journalist who worked closely with Pulido, invites Don Benito to a meeting in her home in order to work on the constitution of «la sociedad de Alianza Israelita a la que V. tuvo la bondad de adherirse».196

Beyond the contacts and activities mentioned in these letters, one can only speculate at present concerning further contributions by Galdós. Unlike Juan Valera, who treated the Sephardim sympathetically in two of his novels, and Miguel de Unamuno, who could read Judeo-Spanish books in Hebrew script, Galdós did not write a publishable pro-Sephardic letter to Pulido. Nevertheless, Don Benito's contributions to the cause may have been greater than the extant letters at the Casa-Museo Pérez Galdós indicate, for the Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, in discussing the Pro-Sephardic Movement, mentions only two names: Pulido and Galdós: «The movement... became very popular when a prominent member of the liberal party, Ángel Fernández Pulido [sic] the 'apostle to the Sephardim,' became its leader. Another friend of the Jews was the novelist Benito Pérez Galdós».197

We do know that (in spite of some opposition from conservative political and religious quarters) the Movimiento Pro-Sefardita accomplished much during Galdós' lifetime and, most important, laid the foundations for events which took place later. Sephardic leaders throughout the world replied to Pulido's letters and questionnaire, supplying much data and many photographs. The Sephardic press was supportive, and appropriate personages did indeed become «académicos correspondientes sefardíes» of the Real Academia de la Lengua Española.198 Pulido traveled widely, visited Sephardic communities, conferred with theit leaders, and encouraged youth groups. (His son, who was receiving advanced medical training in Vienna, also helped in these activities.) The Spanish government granted subsidies for Spanish-language schools in Morocco and, to some extent, in the Eastern Mediterranean.199 Sephardic literati were in contact with people like Galdós, sent copies of their works, and sought a market for them in Spain. In 1915 the Universidad Central de Madrid, with the approval of the king, established the Cátedra de Lengua y Literatura Rabínicas and secured the services of the distinguished Sephardic scholar and teacher, Abraham Shalom Yahuda.200 Subsequently, a Sephardic-rite synagogue (Midrash Abarbanel) was opened in Madrid,201 and in 1920, the year Galdós died, there was established in the Spanish capital the Casa Universal de los Sefardíes.202

However, the most important accomplishment may have been that achieved during World War I, for it alleviated much Sephardic suffering and also established the precedent for rescuing Sephardic Jews from the Nazis and their collaborators during World War II. By 1916, Pulido was vice-president of the Spanish Senate, and he and Galdós, along with the most outstanding citizens of the nation, were also members of a group entitled La Liga Española —94→ para la Defensa de los Derechos y del Ciudadano. Among the documents formulated by this group during World War I, two concerned the Sephardim. The first (18 June 1916) complimented the French government on its enlightened treatment of Spanish-speaking Turkish subjects under its jurisdiction. The second, written a short time later, protested to the Italian government the internment of Sephardic Jews in «campos de concentración» as enemy aliens. The league took the view that the Sephardim were, in spite of their citizenship, really much more Spanish than Turkish and, consequently, were in fact «latinos» like the Italians and French. The Italian government replied that it would accede fully to the league's suggestions. On both documents Galdós was the second person to affix his signature.203

The next logical step was to extend protection to the Sephardim by offering Spanish citizenship to all who wished it. This was done in three stages, culminating in 1924, and it became the means by which Spanish consuls throughout Europe were able to save thousands of Sephardic lives during World War II. Spanish officials were most vigorous and successful in defending their Jewish «citizens» in Nazi-occupied Paris, in Vichy France, and in the Balkans. Many French Sephardim were rescued, over a thousand even after being already interned in the Belsen concentration camp. In Greece, four hundred «Sephardi Jews in the Hairadi concentration camp were saved from deportation to Poland by the prompt action of the Spanish authorities. The Madrid government made known its decision to assume the protection of all Sephardi Jews who sought its aid regardless of whether they were in possession of the proper papers or not. This protection was extended to Bulgaria, Hungary, and other parts of occupied Europe where there were Jewish colonies of remote Spanish origin». Concurrently, in French North Africa, life for the Sephardim was hard, but special consideration was extended to «those Jews who were serving as honorary Spanish vice-consuls»,204 a title and status originally proposed in 1904 by Pulido and the pro-sefarditas.

Returning to Galdós, it is significant to note that the most important publications of the Movimiento Pro-Sefardita appeared just prior to and during his writing of the two novels about Morocco entitled Aitta Tetauen and Carlos IV en La Rápita. At that time Pulido was carrying on his publicity campaign in several Madrid newspapers; his six-part series entitled «Los judíos españoles y su idioma castellano» ran weekly in the magazine La Ilustración Española y Americana from 8 February to 15 March 1904 and was published in book form the same year. The following year, during which Galdós finished his two Episodios, saw the publication of Pulido's monumental book, full of photographs and letters, entitled Españoles sin patria y la raza sefardí. In this, as well as in nearly all other such publications, there were letters from Spain's «hijos perdidos» written in the archaic fifteenth-century Spanish used by the Sephardim.

Given the new public interest in and emphasis on the Sephardim and their language, Galdós determined that firsthand research into the 1859-60 military campaign in Morocco would be necessary if his novels were to be truly realistic. Accordingly, he traveled to Tangiers and then planned to go on to Tetuán, Spain's administrative capital and the place where the 1859-60 army had discovered a large Sephardic community. His contact in Tetuán, —95→ arranged for by the diplomat Ricardo Ruiz Orsatti, was to be, appropriately, a Sefardí, Isaac Toledano.205 A storm made it necessary to cancel the trip to Tetuán, however,206 and Galdós returned to Spain without having made the contacts he desired. Lacking firsthand data, he turned for reference to Pedro Antonio de Alarcón's richly illustrated Diario de un testigo de la guerra de África (1859) and relied heavily on it in creating and describing his Sephardic characters.

For Galdós' purposes, Alarcón's work had a particularly significant shortcoming -although the author had lived for a time with a Jewish family in Tetuán, he had made no attempt to reproduce the Judeo-Spanish language spoken in the home. At a time when Spaniards were accustomed to seeing samples of Judeo-Spanish in their newspapers and magazines and were well aware of its distinctness, Galdós, as his country's foremost exponent of the realist aesthetic, felt he must at least attempt to approximate the language that would have been spoken by the characters in his two novels. Thus, for the first and only time in his career, he assembled a number of reference books and amalgamated therefrom his own highly personal, realistic, but often erroneous version of the Judeo-Spanish language.207 Had it not been for the Movimiento Pro-Sefardita and his involvement with it, this interesting experiment would in all probability never have taken place.

University of Kansas. Lawrence, Kansas

—96→ —97→ —98→- 1 -

- 2 -

—99→

- 3 -

—102→

- 4 -

|

SENADO Particular Madrid 22. X, 1909 Sr. Dr. Benito Perez Galdos Mi distinguido amigo: Le agradezco muchísimo la atención de mandarme el diario de Constantinopla con el artículo sobre el idioma judeo español. ¡Es lamentable que en España no nos ocupemos más en este asunto! Aprovecho la ocasión para repetirme una vez mas su affmo amigo y s. s. Ángel Pulido |

- 5 -

|

Constantinople, el 12 del julio 1910. Al Señor Perez Galdoz, R. Hortaleza 132 Madrid, Espagne Muy señor mío, Tomo la libertad de enviarle a Vd con la presente un ejemplar de mi drama historico «Don Isaac» junto una esta recension aparecida en el diario «Jeune turc [Turque]» de nuestra ciudad. De esta y de las recensiones favorables hechas en casi todos los diarios de Constantinopli Vd puede ver el exito que ha acogido mi obra y la opinion de notables parsonajes. Pienso que la occasion seria favorable dados los recentes avenimientos políticos en España, por poner en venta mi drama. Si a Vd le gustase cargarse con la venta por toda la España, seria yo dispuesto a reservarle un esconto de 25% sobre el precio que es de pes. 11/2. Si esta condicion le conviene a Vd rogo responderme al retorno del correo. —103→En la espera de que se dignará Vd a favorecerme con su pronta respuesta soy S. S. S. Q. B. S. M. Sento Semo P.S. El idioma en el que le escribo es el que llamamos «Judio-Español». Vd me dispensará si es algo diferente del castillano, pero espero que Vd ya lo comprehenderá. El mismo Sento Semo Constantinople Poste anglaise |

- 6 -

|

Sr. D. Benito Perez Galdos Querido Maestro El jueves 2 á las seis de la tarde nos reunimos en esta su casa para la constitución de la sociedad de Alianza Hispano Israelita á la que V. tuvo la bondad de adherirse. Le ruego asista por sí ó por su representación y sabe cuanto se lo agradecerá su ferviente admiradora y amiga qlmlle Carmen de Burgos 11 Madera 5 y 7 19 Marzo |